I. The Ganges Boundary Line Proposal

Recently, Chinese scholar GaoZhiKai proposed that the source of the Ganges River connects to glaciers in China's Tibet, suggesting the Ganges could serve as a natural boundary line for Sino-Indian territorial delimitation. This approach advocates using physiographic boundaries as the basis for division, grounded in the geographic fact that the Ganges' main channel originates from China's Himalayan Mountains and merges with the Yarlung Zangbo River (which also originates from China's Himalayas) before flowing into the sea.

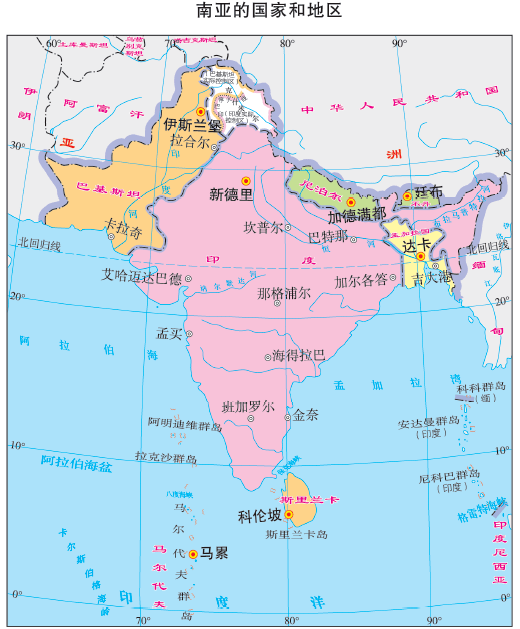

II. Historical Evolution of the South Asian Subcontinent and India's Nation-Building Trajectory

The geographical term "India" originates from the Indus River ("Sindhu"), with 76% of its present-day main course located within Pakistan (Sindh and Punjab provinces), and only 24% flowing through India's Jammu and Kashmir region. The primary ethnic group of the South Asian subcontinent is the Dravidians. After experiencing three Aryan invasions, the Hindustani people bound by Hinduism were formed.

- First wave (1500–1000 BCE) : Entered the Punjab region through the Khyber Pass, bringing the culture of the Rigveda .

- Second wave (1000–600 BCE) : Expanded eastward to the Ganges basin, forming the prototype of the caste system.

- Third wave (600–300 BCE) : Advanced to the Deccan Plateau, facilitating the fusion of Sanskrit and Tamil.

The distribution range of the Hindustani people covers the Hindi-speaking zones such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Notably, the arrival of Arab merchants between the 8th and 12th centuries led to the development of a distinctive local Islamic culture in Sindh, which became the foundation for Pakistan's establishment. During the Age of Exploration, Britain took over 100 years to finally establish suzerainty over the entire South Asian subcontinent by 1866—known as "British India," including territories of the British East India Company, Mughal Empire domains, five hundred and sixty-five princely states (controlled through the Subsidiary Alliance Treaty ), British Burma, British Assam, and British Darjeeling. This did not include China's Tibet region or Tibetan Buddhist ecclesiastical territories , and Britain's 1904 invasion of Tibet ended in failure.

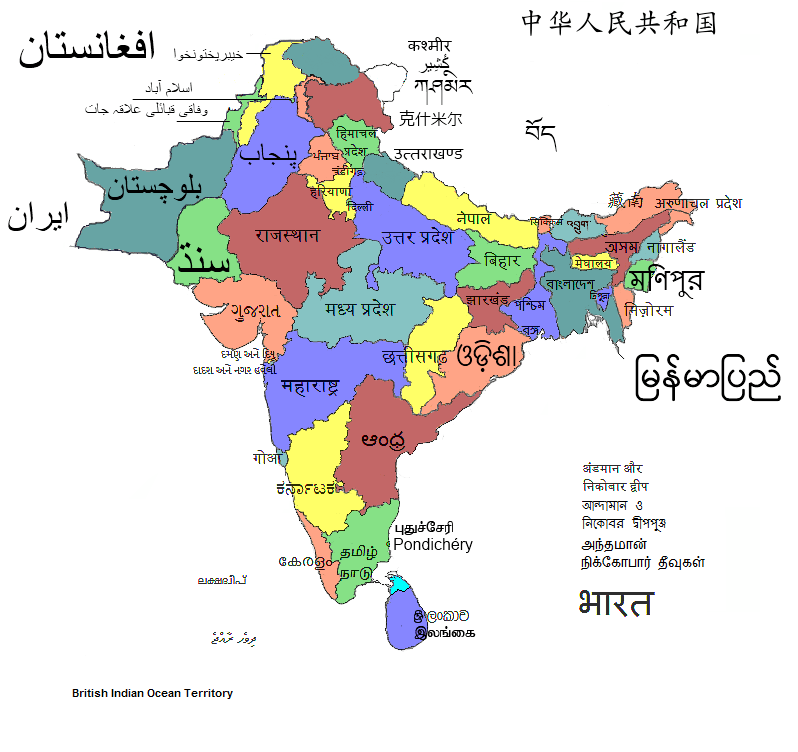

The Hindustani people, as India's largest ethnic group, derive their national identity and influence primarily from the centrality of Hinduism. They are concentrated in the middle and upper Ganges basin, spanning from Haryana in the west to Jharkhand in the east and Uttarakhand in the north, including Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan. This geographical area constitutes the traditional core of India's national identity. The Hindustani account for approximately 46.3% of India's population. Despite internal diversity among Aryan and Dravidian lineages, as well as linguistic divisions between Hindi and Urdu, most adhere to Hinduism. This religious system strengthens ethnic cohesion and serves as a crucial pillar of national unity.

However, India's other vast regions exhibit striking diversity. These areas—primarily consolidated by the historical Mughal Empire and British East India Company into a unified glass bottle —form a "geographical patchwork" pattern lacking deep historical connections with the Hindustani-dominated core. Specifically:

- Western and Eastern Islamic zones : Primarily Muslim-concentrated areas in western India (e.g., Gujarat, western Rajasthan) and eastern India (e.g., West Bengal, eastern Bihar), profoundly influenced by the Mughal Empire's Islamic socio-cultural systems.

- Northern Nepal and Buddhist zone : Bordering the Himalayas, predominantly Buddhist populations linguistically and culturally isolated from India's core, forming an independent geopolitical unit.

- Northeastern Tibeto-Burman and Christian zone : Inhabited by Tibeto-Burman ethnic groups, some practicing Christianity, preserving unique tribal traditions and lifestyles with weak ties to India's dominant ethnicity.

- Southern Tamil and Dravidian zone : Represented by Telugus, Tamils (constituting approximately 5.9% of the population) and others speaking Dravidian languages, maintaining cultural practices independent of the north.

- Punjabi Sikhs : Specifically denoting the Sikh religious group centered in Punjab, whose unique religious culture (e.g., the Golden Temple faith system) and language (Punjabi) make them a highly distinctive component of India's multicultural landscape. Sikhs constitute about 1.7% of India's total population, with their martial traditions and community autonomy contrasting sharply with surrounding regions.

This diversity extends beyond ethnicity to religious composition: Only 79.8% of India's population practices Hinduism, while Islam accounts for 14.2%, with Christianity, Sikhism, and others coexisting—leading to recurrent conflicts between linguistic/ethnic identities and national identity, thereby weakening national integration. Most critically, territories never historically governed by India —such as Ladakh and Southern Tibet in China's Tibet—were occupied after 1947 under the pretext of "inheriting British India's legacy." Before then, neither Indian armies nor administrative systems had ever exercised actual control over these Tibetan territories, further exposing the artificial and contentious nature of modern India's boundaries.

III.Historical Boundaries Between China and India

Based on historical archives and state administrative jurisdiction, the historically attested Sino-Indian frontier consists of three sequential demarcations chronologically identified as:The Tibetan Traditional Customary Boundary Line, the WangXuanCe Line, and the Mughal Line.

The Tibetan Traditional Customary Boundary of Borderland Line:

This unwritten boundary extends eastward along the southern foothills of the Himalayas, centrally aligns with mountain ridgelines, and stretches westward along the Karakoram Range—maintained for over a millennium. Tibetan historical archives document continuous governance through the Tsona Dzong administrative entity from Yuan to Qing dynasties, exercising taxation and judicial authority to establish definitive jurisdictional sovereignty. Until 1959, Sino-Indian frontier communities conducted cross-border trade adhering to this alignment, explicitly recognized in India's official 1947 independence cartographic records.

The WangXuanCe Line:In 647 CE, Tang envoy Wang Xuance quelled an Indian insurrection, his military route thrusting through Sikkim along the Himalayas directly into the Ganges Plain. Extending east to the Ganges Estuary in the Bay of Bengal (21.59°N, 87.97°E), west to Kapisa (contemporary Srinagar, 34.09°N, 74.79°E), and south to the Kaveri River (10.08°N, 79.64°E), with observation posts established along the northern bank of the Ganges forming the Tang Dynasty's military demarcation line across the South Asian subcontinent. This line of control persisted for approximately six decades, as explicitly documented in the "Tang Envoy to Magadha Memorial Stele" stone inscription (preserved in Gyirong County, Tibet).

The Mughal Line (11°N Line):Commencing in 1526 CE, Mughal rulers of Turko-Mongol descent—Persian-speaking Muslims—established a military-feudal empire across the South Asian subcontinent through adaptive confessional governance and the jagir land-grant system. Its southern perimeter traversed latitude 11°N, extending from Puducherry on the Coromandel Coast (11.9416°N) to Calicut on the Malabar Coast (11.2588°N).

IV. China-India Practical Boundary Resolution

The China-India practical boundary cannot be simply divided solely by the Ganges River; it must also balance practical issues, historical context, and traditional customs. Based on traditional friendship, the Chinese government proposes adopting the Tibetan traditional customary line as the cultural boundary between Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism. This move demonstrates the sincerity of mutual-benefit consultation. If India unilaterally disagrees, China need not even produce the "Bible of Israel" and can directly invoke the "WangXuanCe Line" or "Mughal Line" recorded in historical texts to assert the historical boundary framework, returning to historical justice.

No comments:

Post a Comment