Evolution Of Chinese Clothing And CheongSam/QiPao

Chinese clothing has approximately 5,000 years of history behind it, but regrettably I am only able to cover 2,500 years in this fashion timeline.

I began with the Han dynasty as the term hanfu (meaning: dress of ethnic Chinese people) was coined in that period.

Please bear in mind that this is only a generalized timeline of Chinese clothing primarily featuring aristocratic and upper-class ethnic Han Chinese women (the exceptions are Fig. 8 (dancer) and Fig. 11 (maid, due to the fact I couldn’t find many paintings in the Yuan period)).

Han Dynasty:

“In the Han Dynasty, as of old, the one-piece garment remained the formal dress for women. However, it was somewhat different from that of the Warring States Period, in that it had an increased number of curves in the front and broadened lower hems. Close-fitting at the waist, it was always tied with a silk girdle.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 32)

Wei and Jin dynasties:

“On the whole, the costumes of the Wei and Jin period still followed the patterns of Qin and Han.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 54)

“From the costumes worn by the benefactors in the Dunhuang murals and the costumes of the pottery figurines unearthed in Louyang, it can be seen that women’s costumes in the period of Wei and Jin were generally large and loose. The upper garment opened at the front and was tied at the waist. The sleeves were broad and fringed at the cuffs with decorative borders of a different colour. The skirt had spaced coloured stripes and was tied with a white silk band at the waist. There was also an apron between the upper garment and skirt for the purpose of fastening the waist. Apart from wearing a multi-coloured skirt, women also wore other kinds such as the crimson gauze-covered skirt, the red-blue striped gauze double skirt, and the barrel-shaped red gauze skirt. Many of these styles are mentioned in historical records.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 65)

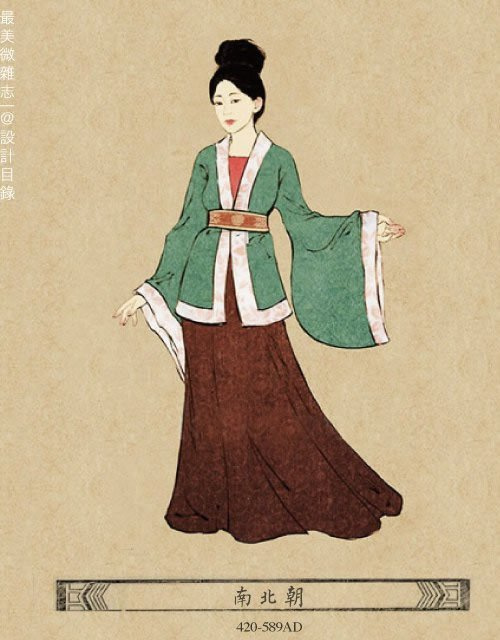

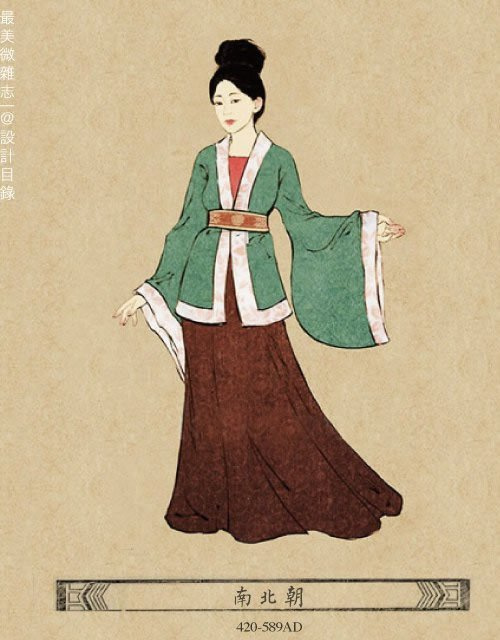

Southern and Northern Dynasties:

“During the Wei, Jin and the Southern and Northern Dynasties, though men no longer wore the traditional one-piece garment, some women continued to do so. However, the style was quite different from that seen in the Han Dynasty. Typically the women’s dress was decorated with xian and shao. The latter refers to pieces of silk cloth sewn onto the lower hem of the dress, which were wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, so that triangles were formed overlapping each other. Xian refers to some relatively long ribbons which extended from the short-cut skirt. While the wearer was walking, these lengthy ribbons made the sharp corners n the lower hem wave like a flying swallow, hence the Chinese phrase ‘beautiful ribbons and flying swallowtail’.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 62)

“During the Southern and Northern Dynasties, costumes underwent further changes in style. The long flying ribbons were no longer seen and the swallowtailed corners became enlarged. As a result the flying ribbons and swallowtailed corners were combined into one.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 62)

Sui Dynasty:

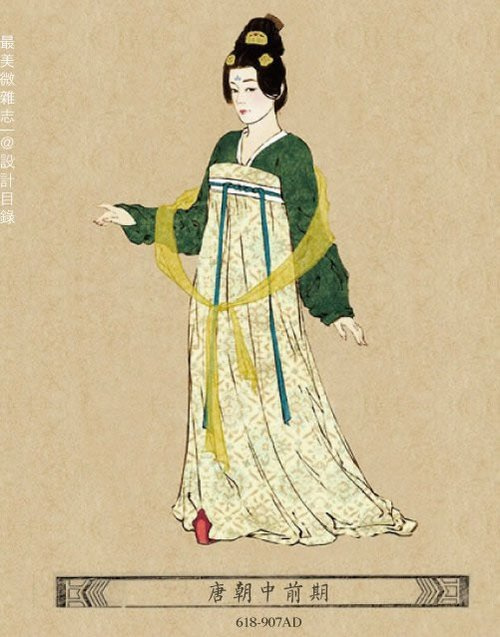

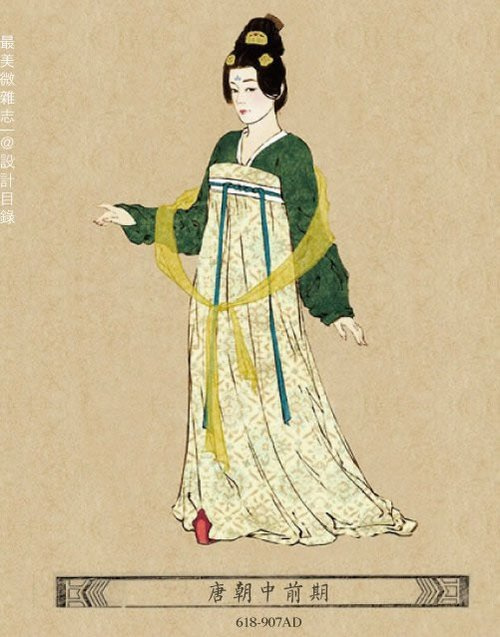

“During the period of the Sui and early Tang, a short jacket with tight sleeves was worn in conjunction with a tight long skirt whose waist was fastened almost to the armpits with a silk ribbon. In the ensuing century, the style of this costume remained basically the same, except for some minor changes such as letting out the jacket and/or its sleeves.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 88)

Tang Dynasty:

“The Tang Dynasty was the most prosperous period in China’s feudal society. Changan (now Xian, Shananxi Province), the capital, was the political, economic and cultural centre of the nation. […] Residents in Changan included people of such nationalities as Huihe (Uygur,) Tubo (Tibetan), and Nanzhao (Yi), and even Japanese, Xinluo (Korean), Persian and Arabian. Meanwhile, people frequently traveled to and fro between countries like Vietnam, India and the East Roman Empire and Changan, thus spreading Chinese culture to other parts of the world.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 76)

“…all the national minorities and foreign envoys who thronged the streets of Changan also contributed something of their own culture to the Tang. Consequently, paintings, carvings, music and dances of the Tang absorbed something of foreign skills and styles. The Tang government adopted the policy of taking in every exotic form whether or hats or clothing, so that Tang costumes became increasingly picturesque and beautiful.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 88)

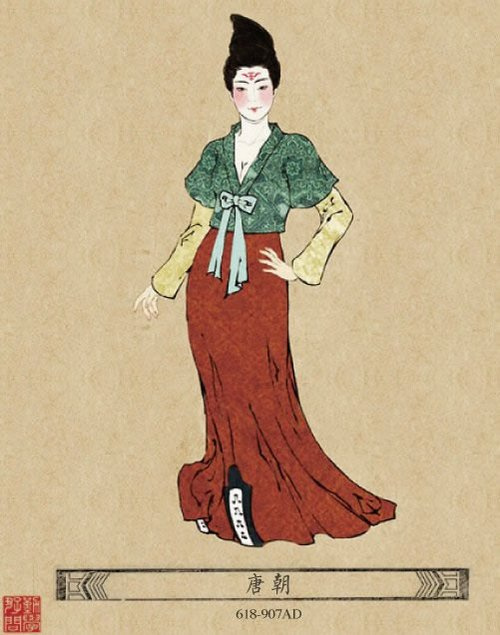

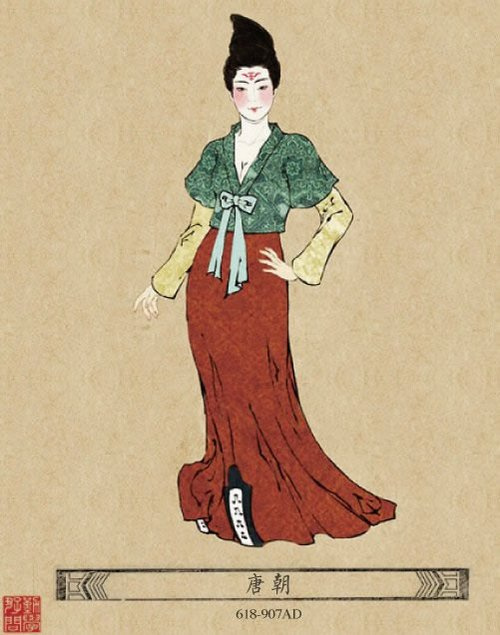

“Women of the Tang Dynasty paid particular attention to facial appearance, and the application of powder or even rouge was common practice. Some women’s foreheads were painted dark yellow and the dai (a kind of dark blue pigment) was used to paint their eyebrows into different shapes that were called dai mei (painted eyebrows) in general.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 89)

“In the years of Tianbao during Emperor Xuanzong’s reign, women used to wear men’s costumes. This was not only a fashion among commoners, but also for a time it spread to the imperial court and became customary for women of high birth.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 89)

Song Dynasty:

“The hairstyle of the women of the Song Dynasty still followed the fashion of the later period of the Tang Dynasty, the high bun being the favoured style. Women’s buns were often more than a foot in height.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 107)

“Women’s upper garments consisted mainly of coat, blouse, loose-sleeved dress, over-dress, short-sleeved jacket and vest. The lower garment was mostly a skirt.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 107)

“Women in the Song Dynasty seldom wore boots, since binding the feet had become fashionable.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 107)

“Although historians do not know exactly how or why foot binding began, it was apparently initially associated with dancers at the imperial court and professional female entertainers in the capital. During the Song dynasty (960-1279) the practice spread from the palace and entertainment quarters into the homes of the elite. ‘By the thirteenth century, archeological evidence shows clearly that foot-binding was practiced among the daughters and wives of officials,’ reports Patricia Buckley Ebrey […] Over the course of the next few centuries foot binding became increasingly common among gentry families, and the practice eventually penetrated the mass of the Chinese people.” (Chinese Chic: East Meets West, pg. 37-38)

Yuan Dynasty:

“Han women continued to wear the jacket and skirt. However, the choice of darker shades and buttoning on the left showed Mongolian influence.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 131)

“After the Mongols settled down in the Central Plains, Mongolian customs and costumes also had their influence on those of the Han people. While remaining the main costume for Han women, the jacket and skirt had deviated greatly in style from those of the Tang and Song periods. Tight-fitting garments gave way to big, loose ones; and collar, sleeves and skirt became straight. In addition, lighter more serene colours gained preference.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 142)

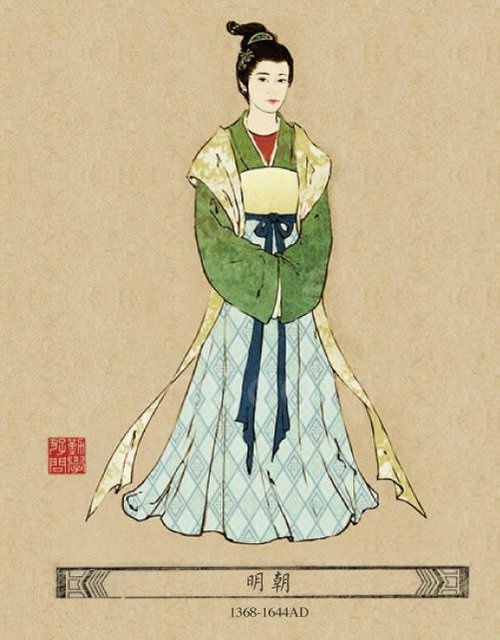

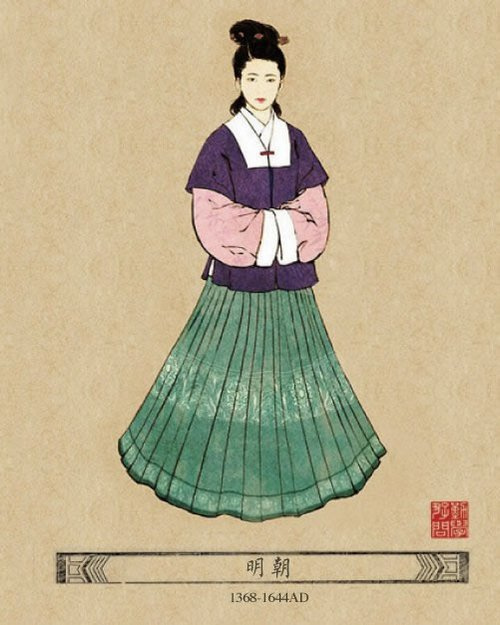

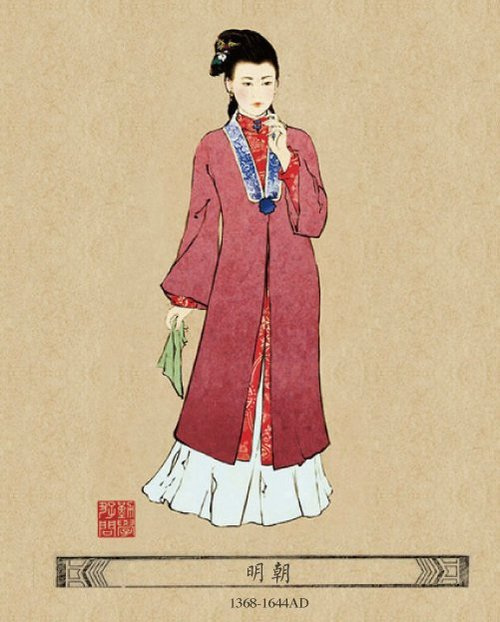

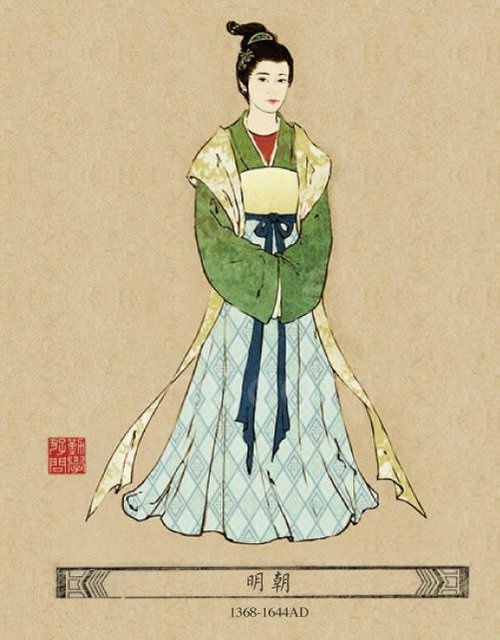

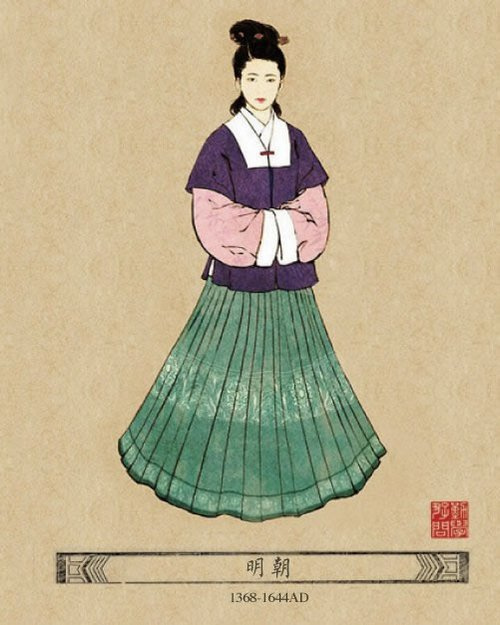

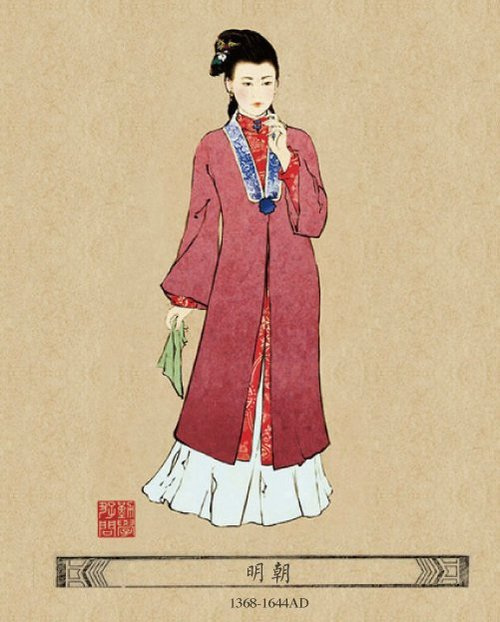

Ming Dynasty:

“The clothing for women in the Ming Dynasty consisted mainly of gowns, coats, rosy capes, over-dresses with or without sleeves, and skirts. These styles were imitations of ones first seen in the Tang and Song Dynasties. However, the openings were on the right-hand side, according to the Han Dynasty convention.” ((5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 147)

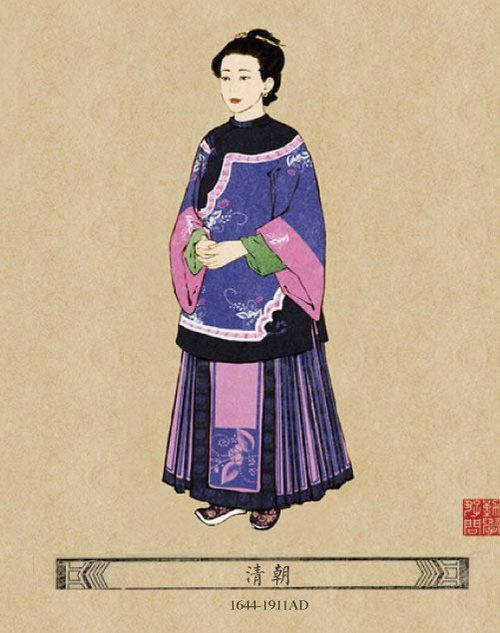

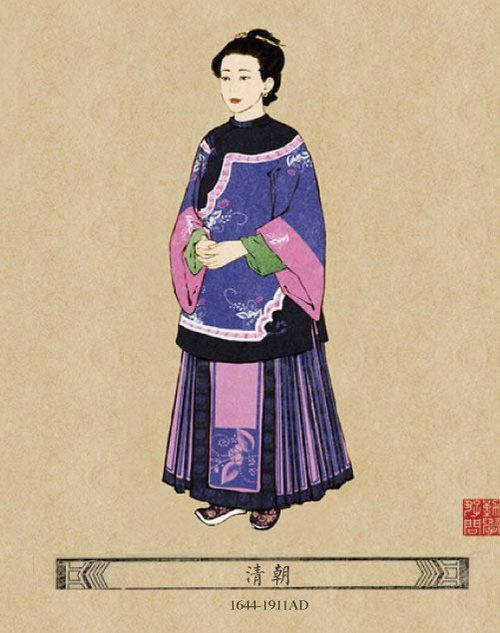

Qing Dynasty

When China fell under Manchurian rule, Chinese men were forced to adopt Manchurian customs. As a sign of submission, the new government made a decree that men must shave their head and wear the Manchurian queue or lose their heads. Many choose the latter.

On the other hand, Chinese women were not pressured to adopt Manchurian clothing and fashions. “Women, in general, wore skirts as their lower garments, and red skirts were for women of position. At first, there were still the “phoenix-tail” skirt and the “moonlight” skirt and others from the Ming tradition. However the styles evolved with the passage of time: some skirts were adorned with ribbons that floated in the air when one walked; some had little bells fastened under them: others had their lower edge embroidered with wavy designs. As the dynasty drew to an end, the wearing of trousers became the fashion among commoner women. There were trousers with full crotches and over trousers, both made of silk embroidered with patters.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 173)

The Manchurians attempted several times to eradicate the practice of foot-binding, but were largely unsuccessful. Manchurian women admired the gait of bound women but were effectively banned from practicing food-binding. Hence, a “flower pot shoe” later came into creation and it allowed its wearer the same unsteady gait but without any need for foot-binding. Photograph of flowerpot shoe here:

[link]

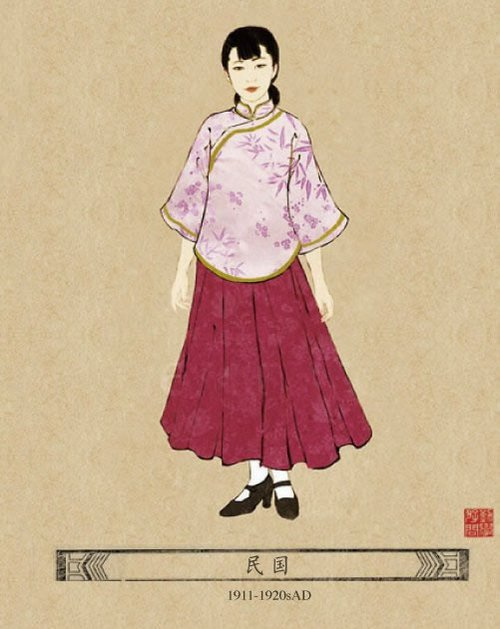

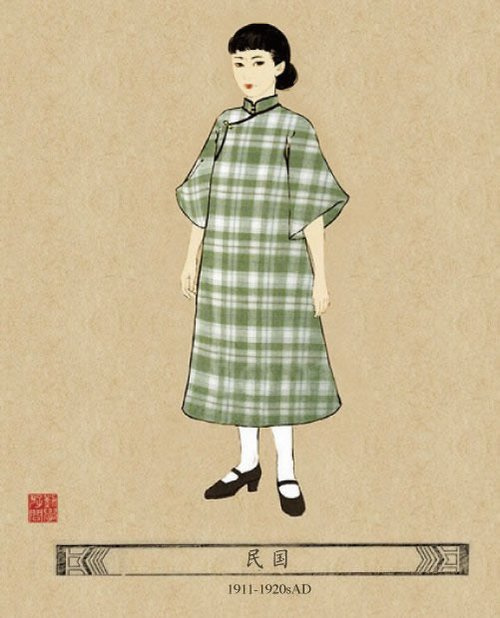

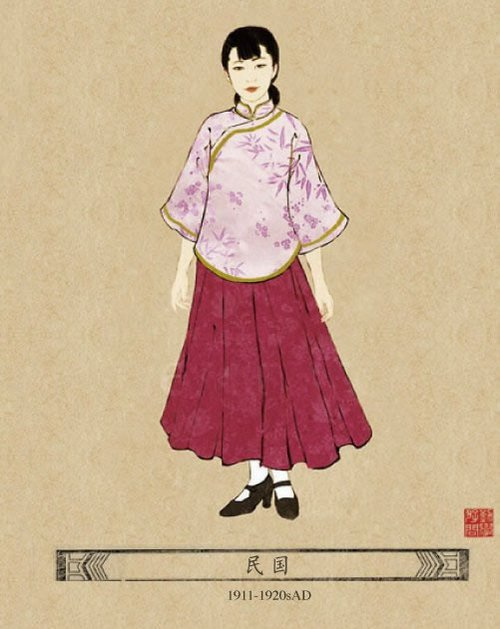

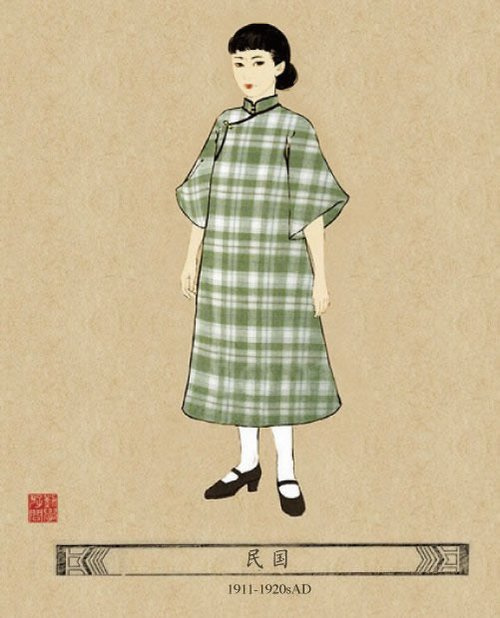

1911-1940s

“Ever since the Tang Dynasty, the design of Chinese women’s costumes had kept to the same straight style: flat and straight lines for the chest, shoulders and hips, with few curves visible; and it was not until the 1920’s that Chinese women came to appreciate ‘the beauty of curves’, and to pay attention to figure when cutting and making up dresses, instead of adhering to the traditional style.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 214)

“The most popular item of a Chinese woman’s wardrobe in modern times was the

qi pao

. Originally the dress of the Manchus, it was adopted by Han women in the 1920s. Modifications and improvements were then made so that for a time, it became the most fashionable form of dress for women in China.

Two main factors account for women’s general preference for the

qi pao

: first, it was economical and convenient to wear. [...] Second, it was more fitted and looked more flattering.” (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 214-215)

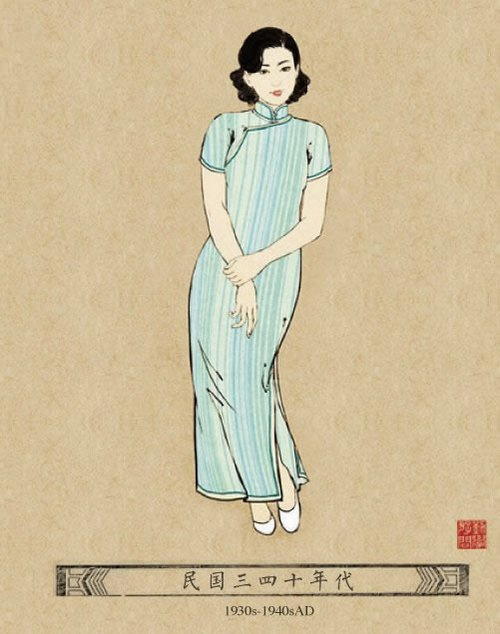

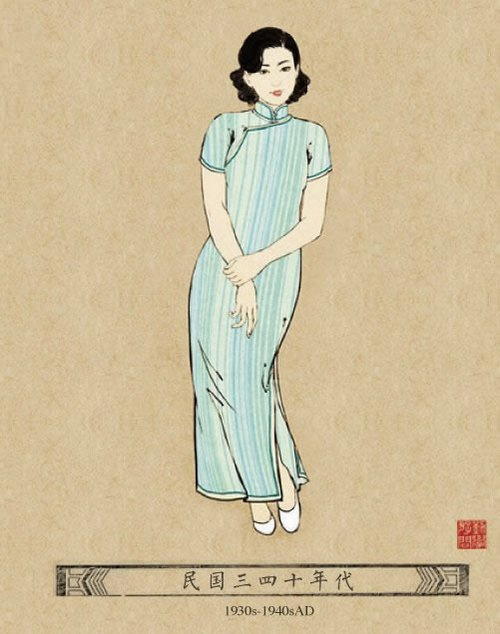

"The

qi pao

underwent numerous changes in style after its first appearance, and by the 1930's it had entirely changed from its original form to become unique among women's costumes." (5,000 years of Chinese Costume, pg. 215)

Women traditionally bound their breasts in the Ming and Qing dynasties with tight fitting vests and continued to do so in the early 20th century. A ban on bound breasts began in 1927, in which the government started advocating for the “Natural Breast Movement”. Despite this, bound breasts still widely continued into the 1930s. The government also banned earrings as it fell under the criteria of deforming the natural body. The 1930s also saw the introduction of the western/French bra come to Shanghai.

“The little vest was designed to constrain the breasts and streamline the body. Such a garment was necessary to look

comme il faut

around 1908, when (as J. Dyer Ball observed): ‘fashion decreed that jackets should fit tight, though not yielding to the contours of the figure, except in the slightest degree, as such an exposure of the body would be considered immodest.’ It became necessary again in the mid-twenties, when the jacket-blouse—a garment cut on rounded lines – began to give way to the

qipao.

At this stage, darts were not used to tailor the bodice or upper part of the

qipao

, nor would they be till the mid-fifties. The most that could be done by way of further fitting the

qipao

to the bosom was to stretch the material at the right places through ironing. Under these circumstances, breast-binding must have made the tailor’s task easier.” (Finnane 163, Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation)

Successful eradication of bound feet would not come until the 1949 when the People’s Republic of China came into power.

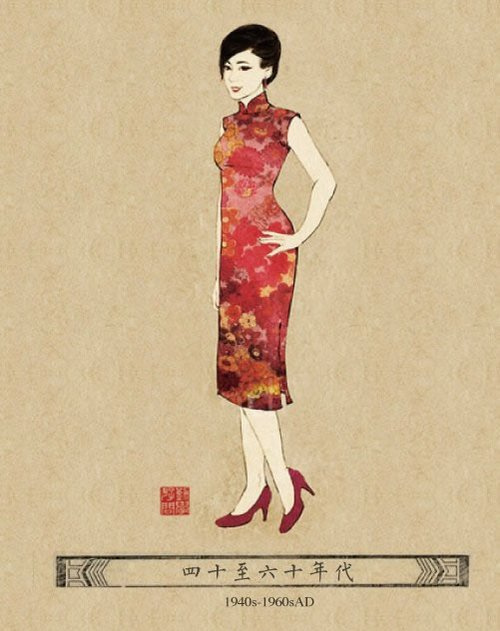

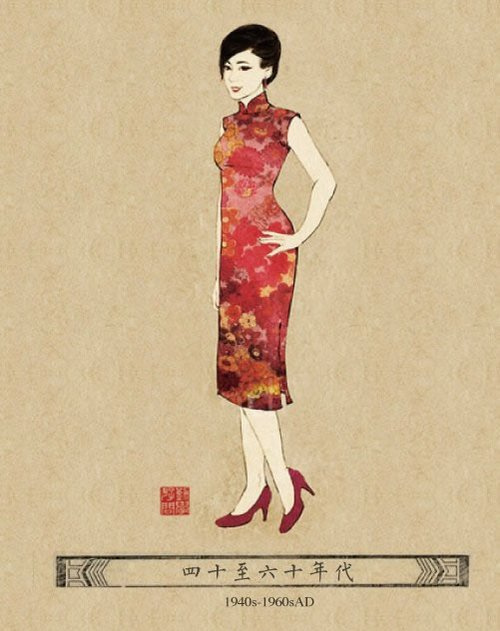

1950s-1960’s

Under the People’s Republic of China, very few mainland women wore the cheongsam, save for ceremonial attire. In this era, clothing became de-sexualized for mainlanders.

It was the flip side in Hong Kong, as the

cheongsam

(Cantonese,

qipao

in Mandarin) continued its function as everyday wear which lasted until the late 1960s. The

cheongsam

in the 1950s and 1960s became even tighter fitting to further accentuate feminine curves. Western clothing became the default after the late 1960s, though the

cheongsam

continued to survive as uniforms for students (who donned a looser and more androgynous version), waitresses, brides, and beauty contestants.

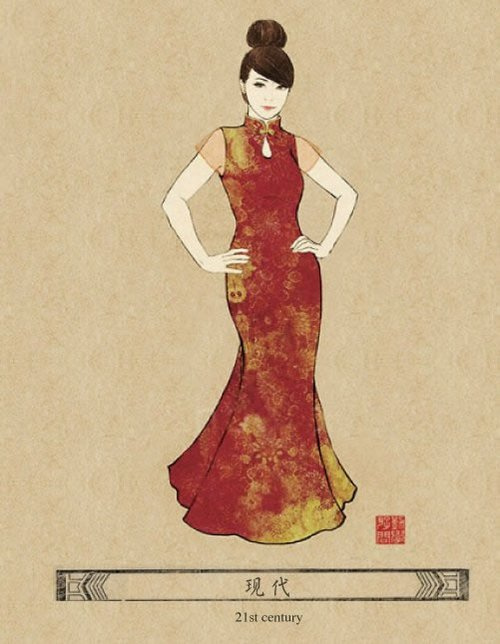

21st century

Designers today are creating new forms of the

qipao

/

cheongsam

. The fish tail appears to be a current popular trend.

More on Cheongsam/Qipao 2.0 here:

[link]

You can also see a more indepth timeline of the Cheongsam/Qipao here:

[link]

The 2010 Cannes Film Festival, FanBingBing , QiPao 3.0

English: Map of the South China Sea, with 9-dotted line highlighted in green (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

English: Map of the South China Sea, with 9-dotted line highlighted in green (Photo credit: Wikipedia)